Every morning when I read through the headlines, I become more and more concerned about the direction the US is heading and wonder how the new authoritarian regime will affect my life in Mexico and my loved ones’ lives still in the US. Doing a little historical digging, here are some of the things that concern me most.

Cracks in the Democratic Foundation

Recent analysis describes the U.S. displaying disturbing similarities to Weimar Germany: political polarization, declining institutional trust, extremist rhetoric, socioeconomic anger, and media fragmentation may be pushing democratic erosion, or worse.

Stanford democracy scholar Larry Diamond sees an accelerating global decline in democratic norms, with slow authoritarian creep in many nations, including the U.S., often underpinned by inequality and disinformation.

Personal Powerusurpation and Legal Erosion

The pattern of executive overreach in America mirrors pre-WWII Germany. Both invoke “emergency” powers to skirt democratic checks. In Germany, the Reichstag Fire Decree and Enabling Act dismantled civil liberties and legislative authority. In the U.S., critics point to an uptick in executive rulings, including invoking obscure laws to detain or deport without full due process.

Another hallmark of rising authoritarianism is institutional capture, where courts, law enforcement, and agencies are stacked with political loyalists. The U.S. has seen growing politicization of the judiciary and federal agencies, echoing Germany’s purge of independent institutions.

Scapegoating, Propaganda, and Cults of Personality

Scapegoating has long been a potent tool for authoritarian regimes, used to unify a majority by targeting marginalized groups. In 1930s Nazi Germany, Jewish people, communists, Roma, and others were falsely blamed for Germany’s troubles and were framed as existential threats to the “Volksgemeinschaft.” Today in the U.S., similar patterns emerge: immigrants, asylum seekers, and religious or racial minorities are increasingly portrayed as threats to national identity or security.

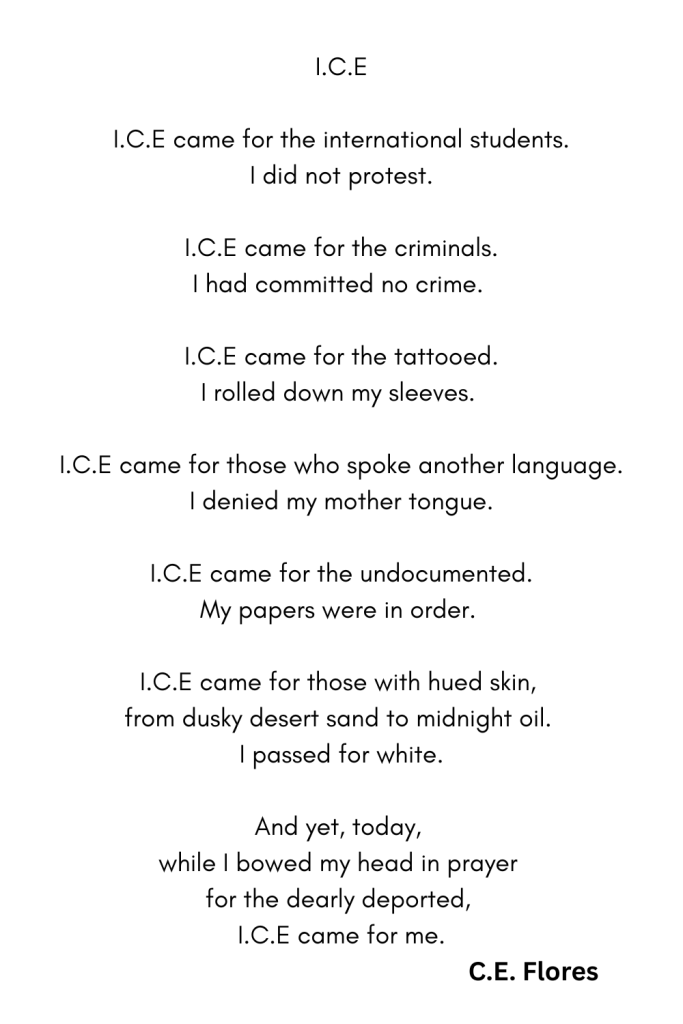

This narrative is reinforced by a vast network of ICE detention centers, now resembling a modern internment system. In 2025, internal planning documents reveal ICE’s intention to nearly double its inmate capacity from 50,000 to over 107,000, which involved adding 125 facilities, including mega-detention and soft-sided “tent” structures, with major private prison contractors like Geo Group and CoreCivic set to profit massively.

First-hand reports reinforce these concerns. Many facilities are described as overcrowded, unsanitary, and neglectful, with detainees forced to sleep on concrete floors, lacking adequate food, water, or medical care. In a harrowing account, a detainee likened conditions to something worse than prison, describing moldy cells and denial of basic needs, while lawmakers seeking oversight have repeatedly been blocked from entering these centers.

The expansion of these detention systems echoes the Japanese American internment camps of World War II. During that era, over 120,000 U.S. citizens and residents of Japanese descent were forcibly relocated and incarcerated without due process, which was justified under wartime hysteria and xenophobia, and later condemned as a grave constitutional violation. Today, the toll of expanding ICE custody, including detaining non-criminal individuals and asylum seekers, is strikingly similar. One report notes that the proposed doubling in detainees would bring numbers “close to the number of Japanese Americans kept in internment camps”.

Beyond physical repression, propaganda plays a crucial role in normalizing such abuses. Just as Nazi Germany used state media and mass rallies to build cults of personality around Hitler, modern political media in the U.S. idolize certain political figures and delegitimize dissent. This framing enables the gradual erosion of democratic norms, painting detention centers as necessary for security, rather than as sites of human rights violations.

All this underscores a brutal truth: once a society normalizes the detention of “undesirable” groups under the guise of security, it erodes the very foundations of rights and protections for all. The U.S. risks repeating historical mistakes unless public scrutiny, media vigilance, and legal oversight intervene.

What This Means for Me as an Expat in Mexico

Mexico as a Historical Haven but Not a Utopian Escape

For decades, Mexico has provided refuge for Americans fleeing political repression and ideological persecution. From anti-war activists of the 1960s–70s to self-exiled journalists, Mexico has been a sanctuary and, increasingly, a destination for U.S. expatriates seeking relative safety or an affordable life. As of 2022, there are an estimated 1.6 million Americans living in Mexico, including retirees, digital nomads, students, and families.

Still, Mexico, while historically hospitable, is not without its challenges. A Los Angeles Times column notes that affluent American expats may unintentionally insulate themselves from local realities, living in privileged bubbles that shield them from poverty, violence, or corruption. “Expats are immune to that… playing the game of life on someone else’s server with cheat codes.”

A major flashpoint has been the sudden rise in anti-gentrification protests in Mexico City’s trendy neighborhoods like Roma and Condesa. In early July 2025, residents marched through long-time urban communities facing skyrocketing rents and cultural displacement triggered by foreign arrivals, often labeled as “digital nomads.” Protesters carried signs reading “Gringo: Stop stealing our home” and “Housing to live in, not to invest in!” criticizing both Airbnb-driven short-term rentals and government-promoted tourism strategies.

Furthermore, Mexico faces its own authoritarian pressures: centralization of political power, weakening of institutions, and militarization of governance. Some analysts argue the country may be drifting toward “competitive authoritarianism.” Executive overreach, judicial reforms, and suppression of dissent muddy the promise of stability for longtime dissidents.

Moreover, political violence, particularly assassinations connected to organized crime targeting candidates, continues to threaten democracy at the local level, complicating political life for both citizens and exiles.

Final Thoughts

Living in Mexico, I’ve crafted a life I genuinely enjoy, built on community, cultural richness, and personal freedom. Despite the challenges, this country has become a place I call home.

Yet, I can’t ignore that the political climate is shifting here as well. Mexico has increasingly shown a willingness to kowtow to U.S. pressure in politically sensitive areas, a dynamic that could strain its autonomy and indirectly affect those of us who have built our lives here.

- In August 2025, Mexico extradited 26 alleged cartel members to the U.S., a move many analysts regard less as a sovereign governmental decision and more as a maneuver to appease U.S. leadership and stave off economic sanctions tied to the fentanyl crisis. This bypassed the typical judicial process, suggesting the extraditions were influenced by Washington’s pressure.

- Earlier this year, Mexico deployed 10,000 National Guard troops along the northern border under Operation Frontera Norte, directly responding to U.S. threats of tariffs linked to migration control, which was a decision seen by critics as reactive compliance rather than proactive defense of national sovereignty.

- Most notably, Mexico is now pursuing constitutional reforms to explicitly protect against possible U.S. military incursions or interventions, an ominous signal that such threats feel plausible enough to require legal reinforcement.

Whether democracy will crack, stabilize, or rebound is unpredictable, making my life in Mexico feel even more precious and fragile. It’s not perfect, but it might be all there is before too long.

*****

Considering a Move to Mexico?

The Woman’s Survival Guide to Disasters in Rural Mexico: A Framework for Empowered Living Through Crisis

In uncertain times, preparation is power. This guide is written for women navigating life in rural Mexico, offering hard-earned lessons, crisis strategies, and resources for building resilience in the face of political, social, and environmental instability. If you’ve ever wondered how to protect yourself, your family, and your future in an unpredictable world, this book gives you the framework to act now.