September is a particularly patriotic month for México.

It begins with the commemoration of the Niños Heroes (Boy Heroes) on September 13th. Our little school had “la mañanita Mexicana” on the 13th (which is also the anniversary of the Congress of Chilpancingo or Anahuac when México declared itself independent from Spain in 1813) and in addition to the typical traditions, honored those cadets that died defending the flag at Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle from invading U.S. forces in during the Mexican–American War in 1847.

In the call and response manner commonly found in the Catholic Church, each teenager’s name was read, and the attendees responded with “Murió por la patria.” (He died for our country.)

The Niños Héroes were:

Juan de la Barrera (age 19)

Juan Escutia (age 15–19)

Francisco Márquez (age 13)

Agustín Melgar (age 15–19)

Fernando Montes de Oca (age 15–19)

Vicente Suárez (age 14)

Each town does things a little differently. In Moroleón, in the afternoon on September 14, there is a caminata (mini-parade) of local horsemen from Moroleón to El Ojo del Agua Enmedio (where we go to get our water supply). This year, my husband participated with Beauty.

My husband all ready for the caminata.

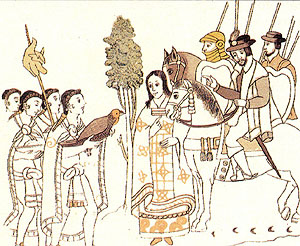

El Grito de Dolores (The Shout from Dolores–a small pueblito (town) where Hidalgo made his call to arms speech) on September 15th, marks the official beginning of the Independence day celebration at around 11 p.m. The church bells are rung and the presidente (mayor) of Moroleón recites El Grito (the shout) with attendees responding with “Viva” to indicate their support.

¡Mexicanos! (Mexicans)

¡Vivan los héroes que nos dieron la patria y libertad!

(Long live the heroes that gave us our liberty)

¡Viva Hidalgo!

(Long live Hidalgo)

¡Viva Morelos!

(Long live Morelos)

¡Viva Josefa Ortíz de Dominguez!

(Long live Josefa)

¡Viva Allende!

(Long live Allende)

¡Viva Galena y los Bravos!

(Long live Galena and the Braves)

¡Viva Aldama y Matamoros!

(Long live Aldama and Matamoros)

¡Viva la Independencia Nacional!

(Long live national independence)

¡Viva México! ¡Viva México! ¡Viva México!

(Long live Mexico)

The church bells are rung again and the pyrotechnic show begins.

In Moroleón, there is a civic parade in the morning on September 16. The members of the presidencia (City Hall) lead the march with la reina de Moroleón (sort of like the homecoming queen) and her escort of charros (horsemen) finishing it off.

The horses, in my opinion, the best part, are at the very end so that marchers don’t have to swerve around poop piles. Most of the civil organizations of the town are represented, from the Down Syndrome club to those of the tercer edad (elderly). Students from the secondarias (high school) and tele-universities and their drum and bugle members also march. It makes for a long and tedious procession.

There is a second parade on either the 27th or 28th of the month to mark the day of the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire which happened September 28, 1821, 10 years after the historic “grito.” I’ve mentioned before, things here in México take much longer than anticipated, including the fight for independence. This parade is open to the primaria (elementary) schools in addition to those that participated in the first parade, therefore, an even longer and more tedious procession. Last year my son was chosen to be part of the escolta (honor guard) for his school. As Los Niños Heroes (see above) died defending the flag, in their honor the members of each school’s escolta (honor guard) are the best and brightest with the highest promedio (grade average). Needless to say, I was one proud mama cheering him on!

Each school has an escolta (honor guard) in the parade.

The kinders (kindergartens) also have a parade, but it is much shorter. It involves no more than 3 times around the plaza but even that is tiring for little legs.

The best part of the parades is the dousing with confetti. Parade marchers that are not honored with the confetti hasta los chonies (all the way to the underwear) experience are those without attentive family or friends in attendance. Bags can be bought for the low, low price of 5 pesos for 2 little bags. I imagine clean up is a drag for the street sweepers though.

If you missed the patriotic events this month, don’t fret. You’ll get another chance in November with the commemoration of the Mexican Revolution!

If you are interested in learning more about the complicated events surrounding the Mexican fight for independence, you can start by watching Hidalgo La Historia Jamas Contada.

************************